MALUNGON, Sarangani (MindaNews / 07 April) — The wife of a Tagakaulo farmhand was cleaning the surroundings of a farm in Sitio Rancho when she accidentally stepped on a snake that immediately bit her leg.

Edmundo Cejar, a former executive who turned to farming, was in disbelief when the Tagakaulo woman, in her 30s “merely dusted off” the venomous snake bite.

It was a cobra, its neck spread when it struck, said Cejar, who moved with his family to this place about a couple of decades ago after retiring from a jet-setting life as senior executive of a Netherlands-based multinational company.

Worried, he tried to bring the snake-bitten woman to a hospital but she declined. She instead walked to nearby bushes, picked some leaves and walked home to attend to her wound in their hut.

The next morning, Cejar was mystified to see the woman back to doing her chores in their yard, like nothing happened.

“She looked like no snake bit her. I was simply dumbfounded,” Cejar told MindaNews.

Venomous snakes like king cobra, or banakon among locals, are known to abound in this town, sitio leader Sonny Vallente said.

Local authorities have no record of deaths from snake bites, but at one time, the local government offered reward money to anyone who can bring a cobra, dead or alive, to the office of the town mayor, Vallente said.

Vanishing cultural practices

Told about the snake bite incident, Renny Boy Takyawan, a Tagakaulo development worker, appeared unperturbed. In their indigenous community, he said, families rely on plants and herbs to cure ailments, including animal and snake bites.

“It is part of our customary healing practices passed on to us by our ancestors. No need to rush to a hospital, it may even take time and delay treatment,” he said.

But Takyawan quickly pointed out that such traditional healing remedies are among the many practices and ways of life of the Tagakaulo that are facing threats of vanishing.

“Even our language has already been influenced by the more dominant Cebuano and Ilonggo languages,” he noted.

Takyawan said they have been exerting efforts to save their customary practices, like their unique food preparations using indigenous ingredients, how to source and store these, which are a huge part of the Tagakaulo’s distinctive way of life.

“Modern culture can wipe out our entire tribe if we just leave things to fate,” lamented Takyawan as he narrated the many challenges Indigenous Peoples (IP) face not only in their village in Lower Mainit but elsewhere.

Open to exploitation and discrimination

The Tagakaulo people are indigenous in Mindanao, mainly inhabiting the hinterlands of Malungon town in this province and along its fringes with Davao del Sur and Davao Occidental provinces.

Tagakaulo, which refers to “people at the headwater,” are known to be animists in general, although there are those who have converted to Islam and Christianity.

Like other ethnic groups, the Tagakaulos’ accommodating nature makes them vulnerable to exploitation, Takyawan said. Their being considerate has led many to be exploited. A number of them have los their farms and precious heirlooms to speculators, ending up in poverty.

Pivotal role of the youth

The youth who must carry on the traditions, he said, often prefer to explore life in urban places, lured there by the glitter of technology and modernity.

Many young Tagakaulo flee their homes to try life in the city. What makes it sadder, he added, is that many of the youth end up being exploited.

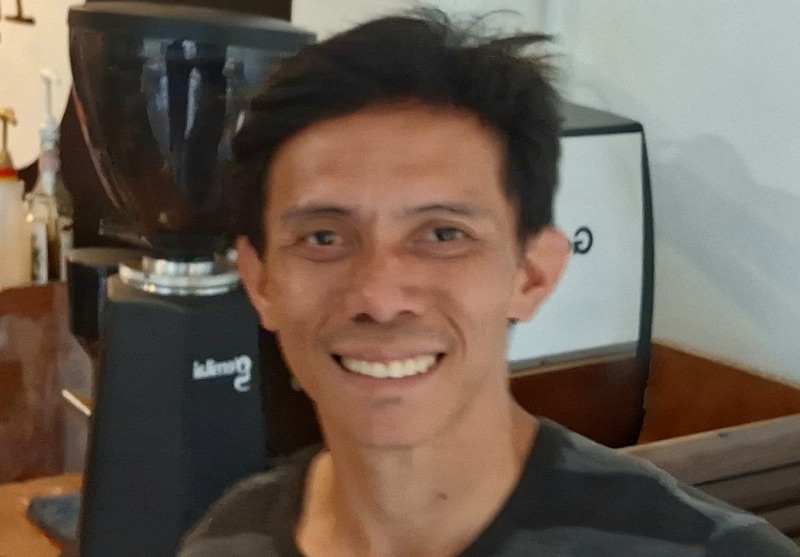

To address the issue, Takyawan launched “Kasambok,” a Tagakaulo word for unity and made it into an acronym for an empowerment project, “Kaalaman Ay Susi sa Mayaman at Buhay ng Katutubong Komunidad.”

The project had encouraging results, but each time, new challenges would arise.

Skeptics will always be there, he opined.

“We are supposed to be done empowering the youth, we are now teaching farmers that farming is not merely planting but a business as well,” Takyawan quipped.

In the last 15 years since it was launched, Kasambok mainly focused on women’s education, teaching farmers to be well-versed in doing business, empowering the youth to be exceptional leaders and conversations on traditional practices and cultural masters.

Kasambok moves with support from Tuklas Katutubo, a volunteer organization of professionals, community leaders and IP advocates, working for the protection and promotion of IP rights and welfare.

Tuklas Katutubo founder Jason Sibug, an Ubo Manobo from Kidapawan City, supported the Kasambok project because of continuing discrimination and lack of recognition, an issue common among IP communities that needs to be addressed.

Tuklas Katutubo works with other IPs nationwide, he said.

With Kasambok and Tuklas Katutubo, Takyawan said the youth get to hone and harness their potentials to become “not just mere heads, but leaders with strong leadership skills, highly capable of protecting and preserving our cultural heritage.”

He said the young Tagakaulos must first realize their vital role as youth with serious understanding of their roots and ethnicity for them to see their crucial role to preserve their traditional way of life, customary practices and value systems.

They must also learn to appreciate the Tagakaulo’s history, to look back and learn who were the Tagakaulo heroes, the royalty and their ties to families and the community, he said.

Building strong leaders

Takyawan said the youth must be able to build strong leaders from among themselves to get their communities to adapt to modernity and influences of other cultures.

“We need to be heard, but every time we air our concerns, we are misconstrued and discriminated against,” he said, pointing out that what they do is not for the political ends of anyone.

The kind of leadership that Tagakaulo youth are being exposed to is based on their indigenous governance, quite different from the usual kind of political leadership that many have been used to.

Takbayan explained that becoming an IP leader is not won by a 50+1 count but by a consensus of 90 to 100 percent majority, agreeing for a person to be their leader.

With the current situation, Takyawan said the Tagakaulo people are left with no better choice but to continue working hard to be heard and understood.

“Unless we speak out and be heard, no one would know the Tagakaulos exist,” said Takyawan. (Rommel G. Rebollido / MindaNews)